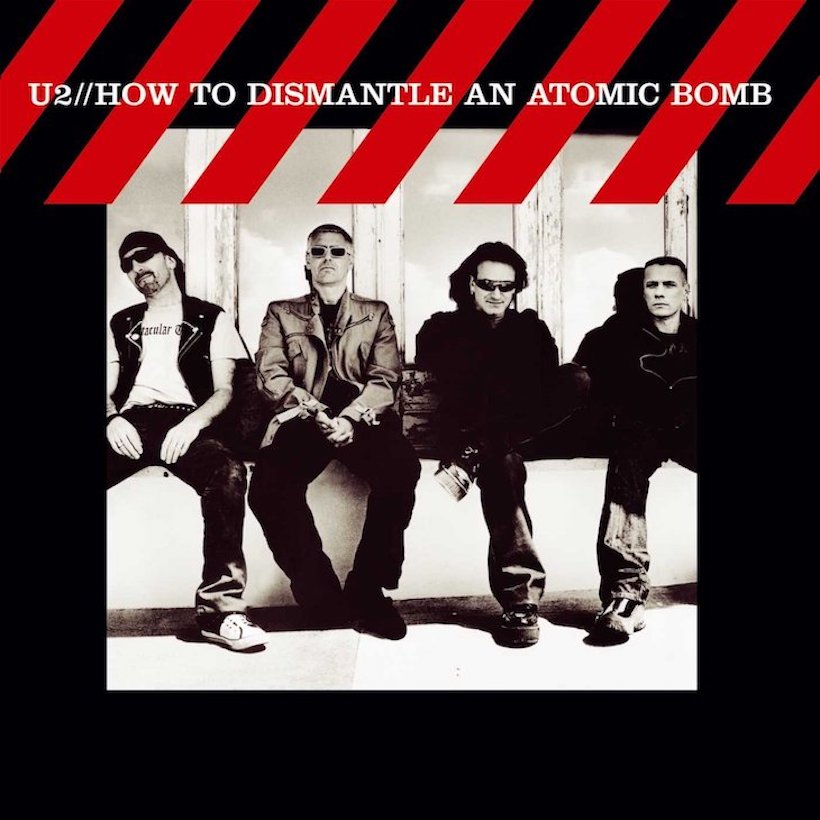

How To Dismantle An Atomic Bomb was an album that not only led to three more Grammy Awards for U2, but heralded their momentous arrival in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. From the very first sound of Larry Mullen Jr.’s sticks and Bono’s count-in to “Vertigo,” there was no room for doubt that they were in the mood to complete the circle back to being the uncompromising rock’n’roll band we first knew.

The beginning of this 11th studio album project was fuel-injected with the momentum of the massively successful Elevation tour, itself a celebration of the rapturously-received All That You Can’t Leave Behind record. U2 were not about to relinquish the crown they had worked so hard for, but as almost always, there would be plenty of challenges to negotiate before they could unveil the results of their latest studio exploits.

New songs for Bomb (named after a lyric in its closing song, “Fast Cars”) started to arrive swiftly when they unpacked their Elevation suitcases, and recording began in the south of France. The resolution to make a definitive rock’n’roll record was unshakeable, but the target of hitting the Christmas 2003 release schedule came and went, and soon Steve Lillywhite was jumping aboard as the album’s new principal producer.

Lillywhite was just the link with U2’s lean and formative persona that was required. He was chief among a cast of eight production contributors that included further longtime confidants Daniel Lanois, Brian Eno and Flood, and newer collaborators Jacknife Lee, Nellee Hooper, and Carl Glanville.

Not for the first time, the band had recordings of the work in progress stolen, which in the new digital era was an even greater security issue. But, for all the delays, the overriding victory lay in a new set of songs that had plenty enough vigour and sparkle to stay the course. As its features became clear, Bono was getting the strong impression that this could be the best U2 record.

“It started out to be a rock’n’roll album, pure and simple,” he said. “We were very excited that Edge wasn’t sitting at the piano or twiddling a piece of technology, because he is one of the great guitarists. Halfway through, we got bored, because it turns out you can only go so far with rifferama. We wanted more dimension.

“Now you’ve got punk rock starting points that go through Phil Spectorland, turn right at Tim Buckley, end up in alleyways and open onto other vistas and cityscapes and rooftops and skies,” Bono continued. “It’s songwriting by accident, by a punk band that wants to play Bach.” Adam Clayton added that a lot of the tunes were “a kick-back to our very early days. It’s like with each year we have gathered a little bit more, and this is what we are now.”

The calling card was the unstoppable “Vertigo,” the sort of definitive U2 single to give “rifferama,” as Bono called it, a good name. It was one of the earliest ideas for what became How To Dismantle An Atomic Bomb, a riff conceived at The Edge’s house in Malibu that immediately sounded like something from the annals of classic rock, somewhere between Zeppelin and the Stooges, but with a 21st century vitality that was entirely custom-made.

“Vertigo” landed in early November 2004, and established the band’s lasting relationship with Apple when it was featured in a commercial for the iPod. The song smashed straight to No. 1 in the UK, their sixth chart-topping single. It repeated the trick around much of Europe, and its presence would continue to be felt for years: both in the title of the ensuing world tour and in its reaping of three Grammy Awards, including one for its video.

Two weeks later, when the album arrived, it was clear that U2 had outrun all of the misfortune to complete a record full of new signature tunes. Underpinned by rock guitar, they came in a wide variety of moods and tempos, from loud and extrovert on “All Because Of You” to contemplative on “Sometimes You Can’t Make It On Your Own.” The latter song was, said NME, a “gentle strum of determined rhythm that grows with a mastery that is almost beyond compare.”

Indeed, the album was immersed in that rare spirit that this quartet had developed over decades by now: never to be afraid of thinking big, with inspiring songs that put their arms around their entire world of devotees. As ever, the response could be measured in multi-platinum: quadruple in the UK and Australia, triple in the US (where it instantly hit the top on December 11) and No.1 just about everywhere.

“All Because Of You,” “City Of Blinding Lights,” and “Sometimes You Can’t Make It On Your Own” all became significant singles through the first half of 2005, by which time the band were well into the Vertigo tour, all 26 countries and 129 shows of it.

Read the stories behind each of U2’s studio albums revealed in sequence at the band’s Essentials page.

The first stages were in the arenas and stadia of North America, with support by Kings of Leon, followed by a European run through the summer. A second run in North America took them clean through to Christmas 2005, then came South America, with a final excursion to Australia, New Zealand and Japan late the next year. “They went out guns blazin,’” enthused one fan at the final night under the stars in Honolulu, nearly 21 months after the opening Vertigo date.

Listen to the best of U2 on Apple Music and Spotify.

As with every previous endeavour, U2 emerged from the album and the tour all the wiser. “We make mistakes all the time,” said Mullen. “We’re very slow learners, but we do learn. The only way we got to this record was by going down that road. Some mistakes have been our saving grace.”

Buy or stream How To Dismantle An Atomic Bomb.