Nowadays it would be called “identity theft”, but when he took the name Sonny Boy Williamson in the early 40s – a moniker already held by a distinguished blues singer and harmonica player who had been born in Tennessee on 30 March 1914 – the man born Aleck Ford, in Glendora, Mississippi, knew exactly what he was doing.

The cynical act of mimicry was designed to further his career, and, decades later, the exploit prompted a funny and moving song on Randy Newman’s excellent album Dark Matter. On “Sonny Boy,” Newman sings from the perspective of the man now known as Sonny Boy Williamson I, about how “This man stole my name/He stole my soul.”

Who was Sonny Boy Williamson II?

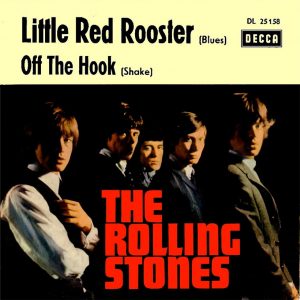

Sonny Boy Williamson II, as he is now titled, is admired by musicians as esteemed as Van Morrison, Eric Clapton, and The Rolling Stones for his songwriting and his ability to conjure a rare and richly innovative tone from his harmonica. But he was one of the biggest rogues in music.

The facts of his life are mired in mystery – his birthdates vary from 1894 to December 5, 1912 – though it is clear that he was savagely treated while growing up on a plantation in Mississippi. His real name is believed to be Aleck or Alex Ford, and he was the illegitimate son of Jim Miller and Millie Ford (he was Millie’s 21st child). Aleck was given the nickname Rice as a boy, supposedly due to his love for milk and rice, and growing up he was known as Rice Miller.

As a teenager, he was often in trouble with the law. Sonny Boy Williamson drifted around the Deep South using the name Little Boy Blue as he played at juke joints and house parties. It was after him that Mick Jagger and Keith Richards named their first band in 1961 – Little Boy Blue And The Blue Boys.

He got his big break in 1941 when he hustled his way into a radio show for the manager at KFFA radio station in Helena, Arkansas. He and guitarist Robert Lockwood auditioned for the executives of the Interstate Grocery Co, who agreed to sponsor the King Biscuit Time show. In return for promoting the company’s flour products, the musicians were able to advertise their nightly gigs. Here is where things become a bit murky, though, because, at some point early on in the show’s history (November 1941-44), Rice Miller adopted the name Sonny Boy Williamson. He and Lockwood can be seen performing together in this silent footage taken from King Biscuit Time.

Who came up with the lie?

It is simply not known who came up with the deceit. Some people have claimed it was the musician’s idea, some claim that Interstate Grocery Owner Max Moore came up with the plan as a ruse to market his goods to African-Americans who liked the blues. The original Sonny Boy Williamson was already a well-known figure (he had scored a hit with his song ‘Good Morning, School Girl’ back in 1937), and blurring the identities of the two performers was an astute (if underhand) tactic.

Sales of King Flour soared and the company started using drawings of Sonny Boy Williamson II on their bags to promote Sonny Boy Corn Meal (he was sitting on an ear of corn and holding a piece of cornbread instead of a harmonica). He would sing little ditties to the company and earn appearance fees opening grocery stores around the state.

What happened to the original Sonny Boy Williamson?

Perhaps everyone involved believed that because the show was broadcast in the South it would not come to the notice of the real Sonny Boy Williamson – John Lee Curtis Williamson – but word of the deception reached him, and the Chicago-based musician went to Arkansas in 1942 to confront the man who had stolen his name. Lockwood was later quoted as saying that Williamson II “chased” the original Sonny Boy out of town.

Sonny Boy Williamson II was a fearsome-looking man. He had large hands and feet, stood six feet two inches tall, and had a history of violence. This writer’s late mother – who photographed him at Heathrow Airport in the 60s – later remarked to me that she remembered his particularly “menacing” eyes. Newman’s ghostly character sings about “this big old ugly cat, twice my size.”

The original Williamson was scared off from challenging him again, and their identities became even more blurred when John Lee’s life was cut short after he was stabbed to death in Chicago in 1948.

How influential was Sonny Boy Williamson II?

With his namesake dead, the new Sonny Boy Williamson’s career went from strength to strength. In the 50s he recorded a host of blues classics, including “Cross My Heart,” “Eyesight To the Blind,” “Nine Below Zero,” “One Way Out,” and “Bye Bye Bird.” Some of his songs, such as “Don’t Start Me Talkin’,” “Keep It To Yourself,” and “Take Your Hands Out Of My Pocket” reflected his guarded, suspicious nature.

As for Sonny Boy Two

The man who stole my name

He went on to glory, fortune and fame

He’s the one who went to England

Tried to teach those English boys the blues

So sings Newman of the influence Sonny Boy II had on British musicians when he toured with Muddy Waters and Memphis Slim in the 60s. “I’m the original Sonny Boy, the only Sonny Boy. There ain’t no other,” he told British interviewers on his tour in 1963, trying to convince them that he had been the first to use the stage name. That he was doubted had something to do with the heavy drinker’s penchant for telling tall tales – including a claim that Robert Johnson had died in his arms.

An interview Robert Plant gave to Rolling Stone magazine highlighted the blues star’s irascible nature. Plant loved going to blues festivals and, aged 14, he introduced himself to the legendary harmonica player at a urinal. Williamson responded with a curt “f__k off”. Plant reportedly then snuck backstage and helped himself to Williamson’s harmonica.

For all his character flaws, Williamson, who died on May 24, 1965 (possibly in his early 50s), impressed his fellow musicians. BB King called him “the king of the harmonica,” and there is no doubting the brilliance of songs such as “Eyesight To The Blind” and “Help Me.”

In an interview with Pitchfork, Randy Newman said that the quality of the music of the real Sonny Boy – especially songs such as “Good Morning, School Girl” and “Jackson Blues” – should not be forgotten, before adding: “I root for Sonny Boy I, of course, but the second guy was just as good, or better. I just think it’s sh__ty that that guy would do that!”