In 1957, 31-year-old Miles Davis – a veritable icon of cool – was the hottest name in jazz. Columbia, the trumpeter’s new label, issued his first two LPs for them that year (’Round About Midnight and Miles Ahead, the latter a landmark orchestral project with Gil Evans), and if that wasn’t enough for the man’s growing legion of fans, Davis’ old label, Prestige, were emptying their vaults, releasing three different recording sessions, under the titles Walkin’, Cookin’ and Bags’ Groove. And in December of that year, Miles recorded one of his most groundbreaking albums yet, the soundtrack to a French film noir, Ascenseur Pour L’Échafaud.

Listen to Ascenseur Pour L’Échafaud on Apple Music and Spotify.

Despite his success as a recording artist, Davis was having trouble keeping his band together. In the spring of 1957 he had dismissed saxophonist John Coltrane and drummer Philly Joe Jones because of their drug addictions, bringing in, respectively, Sonny Rollins and Art Taylor to replace them. Their stay was, however, brief. Belgian saxophonist Bobby Jaspar then made a fleeting appearance in Miles’ band, while Tommy Flanagan took over from departing pianist Red Garland.

In October 1957, Miles brought in the impressive alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley to take Jaspar’s place. Pleased by Cannonball’s presence and abilities, Miles now believed that, if he could entice Coltrane back (the saxophonist had, by this time, kicked his drug habit and was playing better than ever with Thelonious Monk) he could expand his quintet to a sextet, which might result in his finest band ever. “It wasn’t ready to happen yet, but I had a feeling that it would happen real soon,” he wrote in his 1989 memoir, Miles: The Autobiography.

Miles Davis in Europe

While Miles pondered how to rejig his working group and bring some stability back to the line-up, he got an invitation to go to Europe as a guest soloist. He didn’t need any persuading to leave America, where black musicians had to fight racism on a daily basis, and were constantly being hassled by the police. He’d been to Paris before, in 1949, with Tadd Dameron and Charlie Parker, and claimed the experience “changed the way I looked at things forever”. Miles saw how European audiences regarded black musicians with respect. “I loved being in Paris and loved the way I was treated,” he said, recalling with fondness his first European sojourn.

Anticipating a similar warm reception, Miles arrived in Paris in November 1957 and was picked up at the airport by promoter and jazz enthusiast Marcel Romano, who had booked the trumpeter for a three-week tour of Europe that would include concerts in Brussels, Amsterdam, and Stuttgart, as well as the French capital. Unbeknown to Miles, Romano had planned to feature him in a film about jazz, though the project was canceled before Miles’ arrival. By chance, however, film technician Jean-Claude Rappeneau, whom Romano was going to hire for the aborted project, revealed to the promoter that he had been working on a feature film by a young director called Louis Malle, who happened to like jazz. He suggested that Romano approach Malle about Miles providing the soundtrack.

Planning the soundtrack

This idea was uppermost in Romano’s mind when he went to pick up Miles. “I told Miles about the project when he arrived at the airport,” he revealed in a 1988 interview. “He seemed at once very interested and we made an appointment for a private screening. Miles had us explain details of the plot to him, the relationship between the various characters, and he also took a few notes. The actual session wasn’t due to take place for another fortnight.”

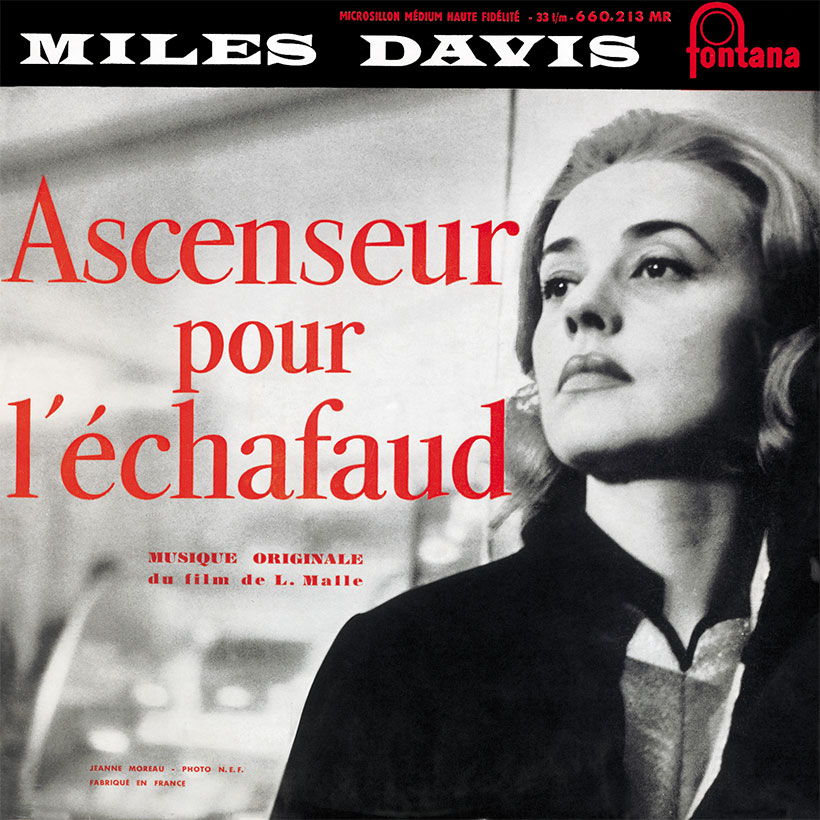

In his autobiography, Miles claimed he was introduced to Louis Malle via French actress Juliette Gréco, whom the trumpeter had first met in 1949 and had a romantic liaison with. He was keen to contribute to the film, titled Ascenseur Pour L’Échafaud (known as Frantic in the US and Lift To The Scaffold in the UK), a thriller which starred Jeanne Moreau and Maurice Ronet as lovers who conspire to kill Moreau’s husband and then face some sobering consequences. “I agreed to do it and it was a great learning experience,” Miles wrote in his autobiography, “because I had never written a music score for a film before.”

As the tour only took up a few days during the three weeks Miles was in Paris, the trumpeter was able to spend some time working on the score. “I would look at the rushes of the film and would get musical ideas to write down,” he explained. Marcel Romano recalled, “Miles had all the time he wanted to think about the recording; he’d asked for a piano in his hotel room, and when I called on him I could see he was working hard in a very relaxed way, writing down a few phrases. I heard bits of themes that were used later in the film, so he had a few melodic ideas before he went into the studio.”

Accompanying Miles at his European concerts were tenor saxophonist Barney Wilen, pianist René Urtreger, bassist Pierre Michelot and an American drummer then living in Paris, Kenny Clarke. According to Michelot, speaking in a 1988 interview, “The session took place after the European tour, so we were used to playing together.”

Recording the soundtrack

On Wednesday, December 4, 1957, at 10 pm, Miles and the other four musicians went into Le Post Parisian studios to record the Ascenseur Pour L’Échafaud score. “Jeanne Moreau was there,” remembered Pierre Michelot, “and we all had a drink together. Miles was very relaxed, as if the music he was playing wasn’t important. It was only later that I learned he’d already been to a screening, and that he’d known about the project for several weeks.”

Marcel Romano recalled, “Louis Malle had prepared a loop of the scenes to which music was to be added, and they were projected continuously. All the musicians were concentrating hard.” Bassist Pierre Michelot said that Miles gave few, if any, specific directions, to the other players, and much of the music was improvised over basic structures: “Save for one piece [‘Sur L’Autoroute’], we only had the most succinct guidance from Miles. The whole session went off very quickly.” Four hours later, the music was complete. “Louis Malle seemed quite satisfied,” remembered Marcel Romano. “And so did Miles.”

Though the film is long forgotten, the soundtrack to Ascenseur Pour L’Échafaud (first issued on LP by Fontana in Europe and Columbia in the US) has proved to be one of Miles Davis’ enduring masterworks, as well as being one of his most beautiful and haunting records. His trumpet has never sounded so desolate and forlorn, especially on the opening cut, “Générique,” which is slow, portentous, and peppered with blues inflections. More melancholy still is “L’Assassinat De Carala,” on which Miles’ horn combines with funereal piano chords to depict a murder scene. Brighter moments can be found, however, on the super-fast “Diner Au Motel” and “Sur L’Autoroute,” both of which are propelled by Kenny Clarke’s busy brushwork.

The legacy of the soundtrack

Stylistically, the revered Ascenseur Pour L’Échafaud soundtrack album was also significant because it eschewed the language of bebop, with Miles preferring to adopt a modal vocabulary, in which scales, rather than chords, take precedence. Modal jazz would become highly influential during the late 50s and early 60s, as an alternative to the chordally-dense argot of bebop. It opened up a new gateway to both composition and improvisation, which Miles Davis would explore again on the 1958 track “Milestones” and in much more depth a year later, on the groundbreaking album Kind Of Blue.

In 2018, Miles’ soundtrack to Ascenseur Pour L’Échafaud was reissued in both triple-10” LP and 2CD editions, bolstered with an extra disc of alternate takes (17 in all) that didn’t make the final cut. Though it’s been decades since it was recorded, there’s a timeless quality to the music that means it’s as relevant now as it was back when Miles recorded it in 1957.

Buy the triple-10” LP reissue of Ascenseur Pour L’Échafaud here.