In the 1970s, guitar-centric rock culture largely looked at synthesizer players as nerds who needed to get a life. The following decade, it was the revenge of the nerds. Suddenly the ball was in the guitar slingers’ court.

Sure, there were exceptions. Prog was a sturdy branch on the 70s rock family tree, and it was full of fearsome synth jockeys. And art rock eccentrics like Brian Eno made electronics seem cool within their cultish cohort. But a good portion of 70s rockers – especially on the harder side – remained dismissive of anything you couldn’t pluck or hit. Even later on, artists like Ozzy Osbourne and David Lee Roth routinely toured with offstage keyboardists, so the rest of the band wouldn’t be tainted with uncool synth cooties.

But when the balance of power shifted in the 80s and synths were suddenly de rigueur, plenty of old-school rock acts managed to move with the times and embrace electronics without besmirching their rep.

Rush

Rush might have been among the more likely rockers to go synth crazy in the 80s. In the 70s, they weren’t afraid to slap a synthesizer on a tune if needed, especially on their proggier epics. On “Tom Sawyer” from their 1981 blockbuster Moving Pictures, the synth even takes center stage for a hot minute.

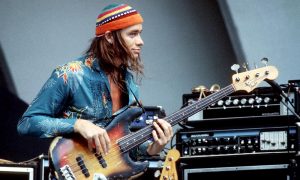

By the time they followed that album up with 1982’s Signals, Rush was ready to take things to the next level. In a 1982 interview with Scene, Geddy Lee – who was doing triple duty on vocals, bass, and keys – said, “Ours was basically a guitar-oriented sound with the rhythm section poking through and an occasional synthesizer line enhancing it. This time, though, we decided on more synthesis…. When I first started, I used a synthesizer bass pedal to fill in the empty spaces in the band. Then I got a Minimoog, and then bigger stuff, and as time went on, the more I learned about the use of sound.”

Geddy wasn’t shy about showing what he’d learned. Burbling synth is the first sound heard on “New World Man,” and it ties the whole track together. Signals’ first single, it would become Rush’s only U.S. Top 40 pop hit. The album’s next single, the alienated-teen anthem “Subdivisions,” was all about the electronics. Geddy’s huge-sounding synth lines just about knock Alex Lifeson out of the box until his lead guitar finally wails near the end of the track.

Styx

Styx was in a similar slot around that time. Like Geddy Lee, Styx singer/keyboardist Dennis DeYoung had no compunctions about leaning into his synth for songs on the artier end of his band’s stylistic spectrum. But the Styx frontline featured two wailing lead guitarists who were hardly spotlight-averse. And for years before 1983’s Kilroy Was Here, there was nary a synth to be found in a Styx hit except the bass figure in “Too Much Time on My Hands.”

A Gallup poll at the end of 1980 declared Styx the biggest rock band in the U.S. They were on top of the world, with nothing to prove and no one to please but themselves. But again like Geddy, DeYoung found that tech advances took him in new directions. Looking back on “Mr. Roboto,” the Kilroy cut that became one of the band’s biggest hits, he told Thom Jennings in a 2010 Backstage Axxess interview that the song was “an unusual composition of mine because it was not based on the piano. It was written with the aid of a Roland synthesizer. I can’t remember the model, but it was the first synthesizer that had an arpeggiator on it, which is like an early sequencer. The way it worked was that you could hold one note down and make it play any number of rhythmic patterns. In this particular case, I held this one program down, and it made a ding ding ding sound and then I added a rhythm piece to it and I came up with ‘Roboto.’”

Jethro Tull

Jethro Tull obviously had exponentially more prog in their past than Rush and Styx put together. But even though they sometimes had two keyboardists, they were far less synth-happy than most 70s progressive outfits, usually either putting Martin Barre’s titanic guitar riffs up front or living up to their status as Rock Band Most Likely to Turn up at a Renaissance Faire.

That began to change with the arrival of new keyboardist Peter-John Vettese for 1982’s The Broadsword and the Beast. The young synthesizer jockey brought modernist electronics to tracks like “Clasp” and “Watching Me Watching You.” But 1984’s Under Wraps would mark Tull’s biggest evolutionary leap.

In between, Vettese worked closely with Anderson on the singer’s synth-drenched solo debut, Walk Into Light. By the time Anderson returned to Tull business, it was synths a-go-go. For the first time, Tull didn’t even have a drummer anymore, that role filled by electronic beats. Vettese’s pop-savvy synth work dominated the disc to such a degree that Anderson’s presence was the only reminder that Under Wraps represented the same band that delivered the guitar-dominated likes of Aqualung over a decade prior.

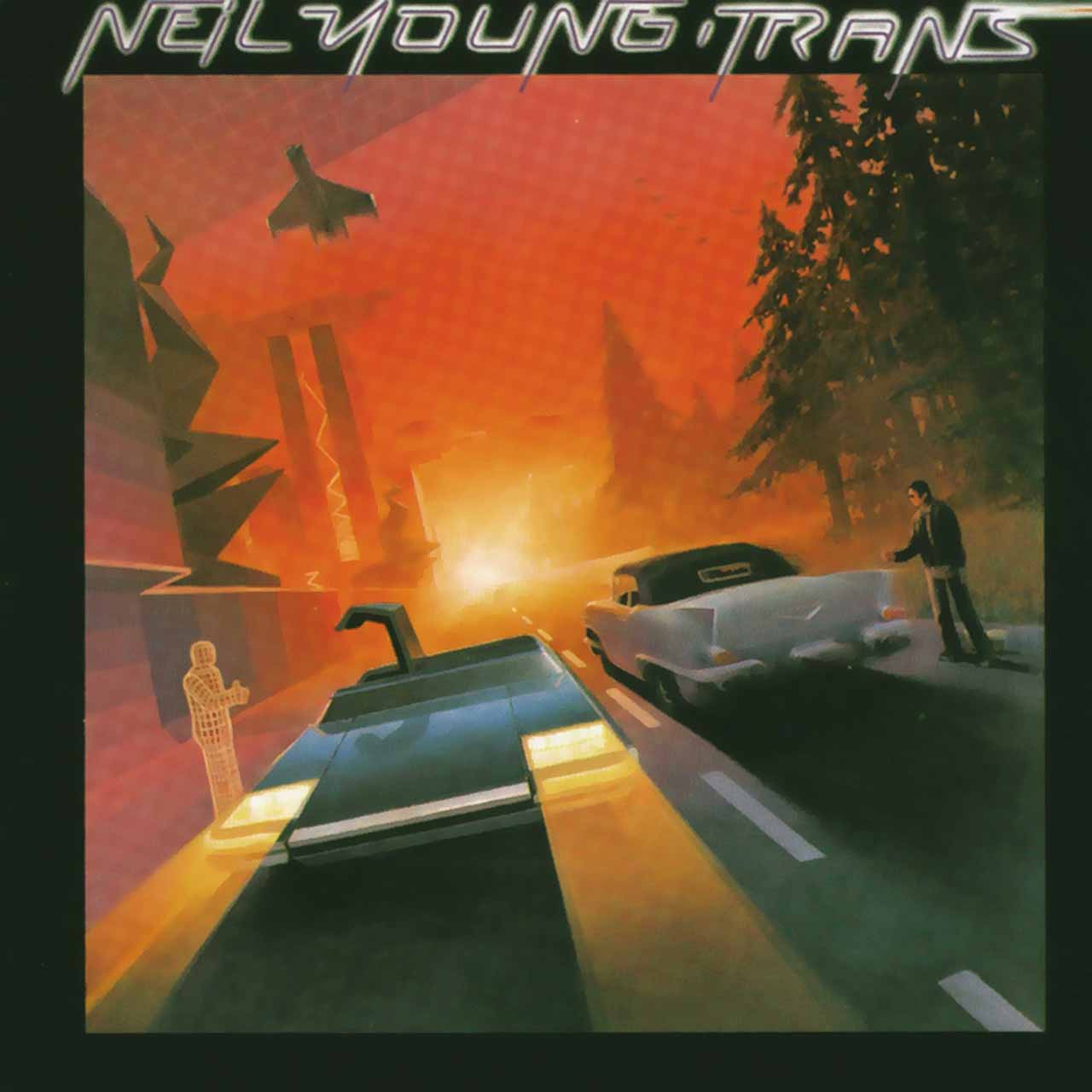

Neil Young

Neil Young was probably the 70s rocker least expected to hitch a ride on the electronic highway. Nobody was more closely associated with gritty, organic roots rock than the Canadian troubadour. But one thing’s always been a given with Young: he always does exactly what he wants. When he kicked off his tenure at Geffen with 1982’s Trans, it was the beginning of a series of off-piste albums underscoring that fact more clearly than ever.

Young would follow the high-tech future shock of Trans with the straight country twang of Old Ways and the rockabilly rumble of Everybody’s Rockin’. But for one album, Young played techno-rock prophet. Even some of the song titles, like “Computer Age” and “Sample and Hold,” displayed his electronic fetish, with robotic vocoder vocals abounding amid stacks of synthesized riffs. Young even redid his old Buffalo Springfield tune “Mr. Soul” in the new mode, which probably had the more hidebound portion of his audience assaulting their speakers in furious confusion.

The sudden stylistic shift came from Young’s family situation. In 1995 he told Nick Kent in a MOJO interview, “we were involved in this program with my young son Ben for 18 months which consumed between 15 and 18 hours of every day we had. It was just all-encompassing, and it had a direct effect on the music of Re-ac-tor and Trans. You see, my son is severely handicapped, and at that time was simply trying to find a way to talk, to communicate with other people. That’s what Trans is all about. And that’s why, on that record, you know I’m saying something, but you can’t understand what it is. Well, that’s the exact same feeling I was getting from my son.”

ZZ Top

Just about the only 70s act with more dirt under their fingernails and grease in their grooves than Young was ZZ Top. When the 80s rolled around they were in a slump, and searching for inspiration. Guitar man Billy Gibbons found it in any unlikely place. In 2015 he told Rolling Stone’s David Fricke, “I saw Devo doing a soundcheck at a Houston club, a country & western bar, of all places. I had heard their first album and kind of dug it. One of the guys in the band was playing a Minimoog, and he did this figure on it [hums a bouncy robotlike riff]. He was just noodling around. But it was enough.”

The experience inspired the herky-jerky, synth-fueled “Groovy Little Hippie Pad” from 1981’s El Loco. Next thing you know, Gibbons is crazy for the synth-pop sounds of Depeche Mode and OMD and the electro-industrial beats of Ministry, and the Top is turning out 1983’s synth-soaked Eliminator. Tracks like “Legs” and “Gimme All Your Lovin’” ran on programmed drums, snappy sequencers, and electronic bass lines and gave the Houston power trio the biggest album of their career.

Van Halen

Another band that bet it all on the classic guitar/bass/drums axis in the 70s but later learned to love the synth was Van Halen. After inventing a new language for the guitar on a string of multi-Platinum albums in his band’s first few years, Eddie Van Halen started wondering what other horizons he could investigate. In preparation for the sixth VH album, 1984, he was having a home studio built, and while awaiting its completion he began playing around with the latest in synthesizer technology.

The result was mega-success with singles like “Jump” and “I’ll Wait,” where Eddie showed he could rock the Oberheim with just as much authority as his guitar. On the latter, Michael Anthony even got into the act, temporarily swapping his bass for a synth with some serious low-end capability.

Wings and Paul McCartney

Early 80s synth developments also seemed to inspire the frontmen of some of the biggest bands of the 70s to step out on their own electronic platform. Though Linda McCartney laid down the occasional ARP Odyssey line with Wings, the band was ultimately about the twin guitar attack perfectly framing Paul’s vocals. His first post-Wings statement was 1980’s DIY one-man-band album McCartney II, a remarkably prescient foreshadowing of trends to come. The percolating electronics on tunes like “Temporary Secretary” and “Front Parlour” heralded the rising synth-pop revolution and even prefigured the electronica boom.

Steve Winwood

There’s scarcely any synth in most of the Traffic discography, but when Steve Winwood moved on from his old band roots-tinged art rock on his first album of the 80s, things were drastically different. Winwood’s 1980 release, Arc of a Diver, translated his soulfulness to electro-savvy ‘80s pop and made him a solo star. The latest in polyphonic synths and drum machines enabled him to do all the heavy lifting on tunes like the poignant smash “While You See a Chance” and the sultry “Spanish Dancer.”

Before the ‘80s were over, synths, sequencers, and programmed drums were as ubiquitous as air. Their absence from a recording was more noteworthy than their presence. But in the early part of the decade, they offered the old guard an opportunity for a fresh, new feel.

Looking for more? Find out how punk and prog are far closer than you think.