Emerald Fennell doesn’t want to give us subtle. She knows it’s seen as the hallmark of “good art”, but her own taste is bolder and more bombastic. “When I think of all of the filmmakers that I love – and all of the things I love: music, books, everything – none of it is subtle,” she says. “Kubrick is not subtle. Hitchcock is not subtle. Britney is not subtle, but my god can ‘Everytime’ kick you in the cunt.”

Saltburn, Fennell’s second feature film as writer-director, definitely isn’t subtle. Like 2020’s Promising Young Woman, for which she earned three Oscar nominations – and won one, for Best Original Screenplay – it’s spiky, audacious and wildly entertaining. Fennell blends and bends genres to tell stories that make us confront unresolvable problems and question our own moral code. Promising Young Woman follows traumatised coffee shop worker Cassie Thomas (Carey Mulligan) as she turns vigilante to avenge her best friend’s rape. It brilliantly captured our post-#MeToo need to have uncomfortable conversations about sexual assault.

Now Fennell is turning her lens to the equally provocative topics of wealth, class and privilege. “I’m interested in power dynamics,” she says when we meet at a London hotel where she is putting in a 9-to-5 stint as her film’s primary ambassador; a few hours after this interview, SAG-AFTRA will end the actors’ strike that has kept Saltburn’s A-list cast off the promo circuit. Fennell is pouring herself a coffee when NME enters the room, and kindly asks if we would like a cup, too. Saying yes proves to be the right decision because listening to this fiercely intelligent director dissect her work is riveting. “Class is such a specific and mad power dynamic,” Fennell continues, “and it’s kind of a fixation in this country.”

On the set of ‘Saltburn’. CREDIT: Warner Bros.

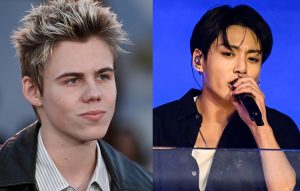

It’s a fixation that Saltburn explores ferociously. Fennell’s second film follows ambitious scholarship boy Oliver Quick (Barry Keoghan) as he becomes obsessed with and befriends Felix Catton (Jacob Elordi), a magnetic aristocrat who glides through life at Oxford University with blithe entitlement. Felix is moved by what he hears about Oliver’s difficult home situation, so he invites him to spend the summer with his own family at Saltburn, their historic country estate. It’s a place so opulent it has a maze in the grounds.

Felix’s feckless parents, Sir James (Richard E. Grant) and Elspeth (Rosamund Pike), welcome Oliver with ostensible warmth, but also view him as a lower-class curiosity. Keoghan’s interloper, though, is far cleverer than any member of the Catton clan, even catty cousin Farleigh (Archie Madekwe), and soon his infatuation with Felix transmutes to them and the house itself. “I wanted to tell a gothic love story and a gothic horror story, I suppose,” Fennell says. “And I wanted to make something about the relationship we have with the things that we desire and how that makes us feel.”

Fennell also wanted to “interrogate the Gothic British country house” trope familiar from books and films such as Brideshead Revisited and Atonement. “That kind of world is all about restraint,” she says. “And I felt like I’d love to see what happens when you un-restrain it to reveal the stuff underneath, which is grubby and fascinating and sexy and troubling.” The results are very funny and very shocking, often at the same time. One of the film’s most scandalous set-pieces, which requires Keoghan to show off his dance moves, is soundtracked by Sophie Ellis-Bextor‘s effervescent pop banger ‘Murder On The Dancefloor’. It’s so wrong it’s genius.

“Saltburn’ is me trying to come to terms with what an embarrassing person I am”

Fennell says this scene reflects her willingness to shun subtlety in favour of cranking things up “to the point where they feel ridiculous or a bit cringe”. “So much of being a director is like, ‘Do I like this? Do I get it? Does it make me feel something?’” she says. “And [that scene] makes me feel something every time. When I watch it, I just feel ready to go outside and murder someone… or have sex with them.”

Saltburn‘s period setting – the film begins at Oxford in 2006 – also lets Fennell look cringe right in the eye. “Wherever you are in time, roughly 15 years ago is never cool,” she says. “And if you’re talking about the richest, most beautiful people in the world and the most beautiful places in the world, you have to find a way of reminding [the audience] that they’re human and live in the same world as the rest of us. You know, that they’re susceptible to terrible tattoos and Livestrong bracelets and bad fake tan and all that stuff.”

The director selected indie bangers from the era carefully: Bloc Party‘s ‘This Modern Love’ and MGMT‘s ‘Time To Pretend’ feature in key scenes, but Arctic Monkeys were vetoed because they’re still “so huge” today. “It was such an interesting time for music, because a lot of the huge bands [back] then did not outlive the time,” Fennell says. “And so it was [a matter of] looking at those bands who are beloved and still make great music, but maybe their big moment was then, so it really fixes you in that time.”

At Saltburn with Barry Keoghan and Jacob Elordi. CREDIT: Warner Bros.

Fennell has a keen feel for the sights, sounds and smells of mid-2000s student life because this was when she completed her own Oxford degree, in English. She describes herself as “absolutely the person [at her college] with a Brideshead fetish” because like “a basic bitch” she fully embraced the romantic Oxford fantasy. “I would be wearing a pair of men’s 1930s trousers and braces,” she says with a laugh. “So much of this film, and so much of everything I make, is me trying to come to terms with what an embarrassing person I am [and] what embarrassing people we all are.”

Though she may wince at her style choices, Fennell can look back at her student persona with a healthy sense of perspective. “I wanted desperately to be thought of as sexy and clever,” she says. “But that’s all any of us ever want, right? For somebody to describe you as sexy and clever. And none of us are – you know, not really. We’re all just kind of cringe.” Fennell relished the famously intense and combative Oxford teaching style, but also enjoyed the baser aspects of student life. “I mean, I was throwing up in my sink a lot like Oliver and just felt a lot of shame,” she says.

While acting in a student play, Fennell was spotted by talent agent Lindy King, who also represents Keira Knightley. She duly launched her professional acting career in 2007 and now has around 20 screen credits, including a cute cameo in Greta Gerwig’s Barbie as heavily pregnant Midge. Perhaps most notably, Fennell played (future Queen) Camilla Parker Bowles in seasons three and four of The Crown, a role which earned her an Emmy nomination.

“Being rich and living in London gives you a deeply unfair advantage”

However, over the last five years, Fennell has focused her energy behind the camera. She was head writer on season two of Killing Eve and wrote the book for Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Cinderella musical. With Promising Young Woman, and Saltburn especially, she has developed what her producing partner Josey McNamara calls a “completely singular” voice. “She is completely fearless and always trying to think of new ways to emotionally connect with people,” he says. “I always want people to walk out of a film and have a conversation about how it makes them feel. Emerald is such a genius at pulling that out of people.”

What Saltburn pulls out of people is sure to be confronting, especially because its examination of privilege comes as we’re grappling with an increasingly pernicious cost-of-living crisis. Does Fennell think this makes it even more timely? “Yes and no,” she replies. “I mean, things exist in and outside of their time. For me, of course [the film is] about absurd privilege, but it’s also about our relationship with that. You know, none of us can stop looking [at wealth and privilege], no matter what the circumstances of the world are.”

Candidly, Fennell admits she is “kind of cautious” when it comes to discussing Saltburn‘s exploration of privilege, partly because she is so conscious of her own. The daughter of top jewellery designer Theo Fennell, she grew up in a loving and financially comfortable household in Chelsea, a neighbourhood that is now synonymous with posh reality stars. “In this industry particularly – but in yours too [journalism] – one of the only ways of being able to make anything at all is if your parents live in London and you’re able to basically work for free for years,” she says. “That gives you a deeply unfair advantage and I’m constantly aware of that.”

Taking a break in Oxford between university scenes for ‘Saltburn’. CREDIT: Warner Bros.

But equally, Fennell doesn’t think it’s “useful” to over-explain her work. “This film is a years-long interrogation of all the ways I think about this stuff, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s straightforward or the ‘last word’,” she says. So, much like Promising Young Woman, it’s a 360-degree examination of issues we can never fully have a handle on? “How can anyone have a handle on this stuff?” she says. “It’s absurd and completely demented to think you could. Every single person’s relationship with everything [like this] is so personal.”

Fennell also believes we’re quicker to presume that a female filmmaker’s work is essentially a “memoir” or “diary” rather than an “exercise of imagination”. “People want to know what you think, and my answer is always the same: I don’t know,” she says. “The cost-of-living crisis is a fucking nightmare. The way men treat women is a nightmare. How do we live in a world where these things exist? I don’t know. And so I make things because I want to talk about them, and because I want other people to talk about them.” There’s no doubt she has succeeded with Saltburn: a film that will make you question your own privilege – and how you feel about people who appear to have it all.

‘Saltburn’ is in cinemas on November 17

Lead image: Alexandra Arnold

The post Emerald Fennell is well aware of her own privilege: “Class is such a fixation in this country” appeared first on NME.