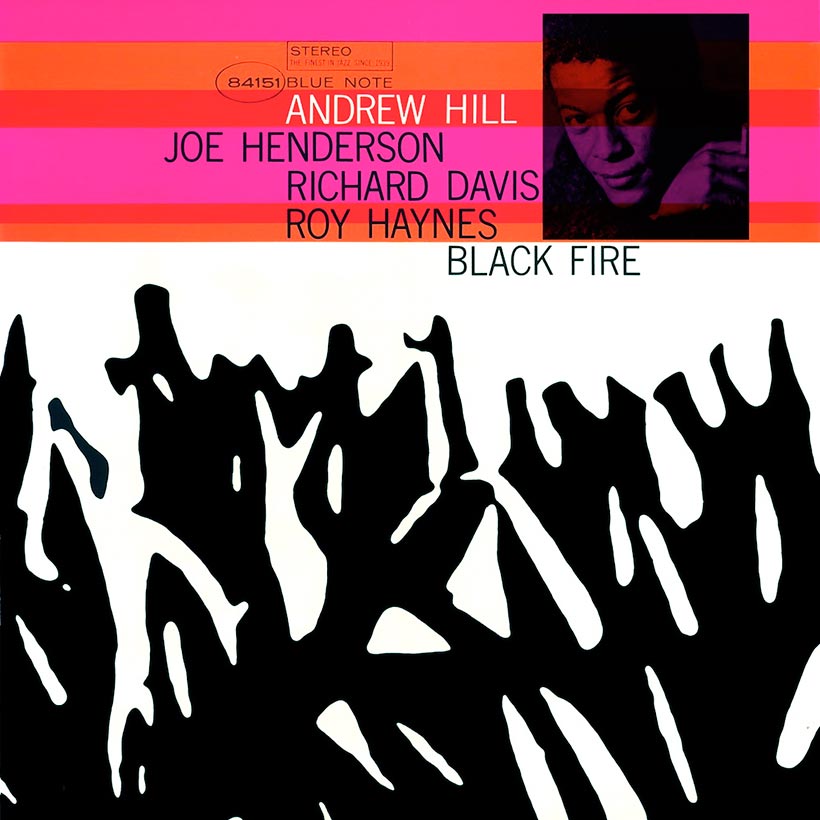

On Friday, November 8, 1963, Andrew Hill walked into Van Gelder Studio at Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, for his maiden recording session for Blue Note Records. Following a second stint at the studio the following day, he emerged with Black Fire. It marked the beginning of what would be the first, and longest, of three separate stints (1963-70, 1989-90 and 2006) with Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff’s iconic New York-based jazz label.

Listen to Black Fire on Apple Music and Spotify.

But anyone that regarded Hill, then a 32-year-old pianist/composer originally from Chicago, as a recording novice was very mistaken. He had, in fact, recorded a brace of 10” singles for the small Ping label, in 1956, and that same year cut a long-forgotten trio album (So In Love) for Warwick, which consisted mostly of standards and didn’t get released until 1960. More significantly, just prior to his debut Blue Note session, he worked on albums by multi-instrumentalist Roland Kirk (before the latter prefixed his name with Rahsaan) and vibraphonist Walt Dickerson. It’s also worth noting that Miles Davis must have held Hill in high regard, as he hired the pianist to play on some of his band’s Chicago gigs in the mid-to-late 50s.

Brimming with passion

Though Black Fire was only his second solo recording, it’s a mature, fully-formed collection of self-penned material revealing that Hill had already discovered his own distinctive voice in jazz. His sui generis approach to melody, harmony, rhythm and compositional structure has no parallel, except, perhaps, in the similarly idiosyncratic figure of Thelonious Monk, also a pianist/composer who created his own personalized form of jazz.

Monk certainly exerted a big influence on Hill, especially in regard to the latter’s angular chromatic melodies and jaunty rhythms, but, as Black Fire reveals, Hill’s concept was entirely individual. In fact, the latter’s take on jazz was so different from the bop mentality that largely prevailed at Blue Note that he found it difficult to find simpatico musicians on the same wavelength. This resulted in a great many of his later sessions for the label (such as Dance With Death and Passing Ships) being shelved until later dates.

Thankfully, on Black Fire, Hill doesn’t have this problem and leads a fine, intuitive quartet that seems to be wholly in tune with him as well as the sometimes exacting demands of his material. The estimable Joe Henderson, renowned for his robust, growling tenor saxophone (and who, in 1963, had just released his Blue Note debut LP, Page One) is the only horn player present, while the rhythm section consists of Hill’s fellow Chicagoan, bassist Richard Davis, and noted drummer Roy Haynes (who, at 39, was the oldest member of the quartet). The latter brought with him much experience and a highly-nuanced polyrhythmic style that would both complement and enhance Hill’s music.

The first notes we hear on the album are Haynes’, coming from his busy hi-hat and cymbal patterns in tandem with Davis’ elastic bass. Together, they announce the opening bars to “Pumpkin,” the first of seven original Hill tunes on the album. The piece boasts a knotty but memorable main theme, enunciated by Henderson’s sax, before Hill takes the first solo; its tumbling sequence of notes epitomizes the composer’s singular piano style. Henderson, meanwhile, navigates his way through the tricky changes with aplomb.

A highly original musical mind

Hill’s piano is more jagged on “Subterfuge,” which sees the 26-year-old Joe Henderson sit out. The song is built on throbbing ostinato rhythms churned out by Haynes and Davis, who are both allowed solo spots. In sharp contrast, the album’s title tune, rendered in a jaunty 3/4 time, finds Henderson back in the fold and is distinguished by a highly infectious Monk-like main theme.

“Cantaros” is different again and defined by a quasi Latin-esque rhythm, though it’s far from conventional: the Hispanic influence is implied rather than stated, and refracted through the prism of Hill’s imagination. “Tired Trade,” meanwhile, has more of a blues feel, though, again, it’s not entirely orthodox. With Henderson dropping out once more, reducing the group to a trio, Hill’s roving piano is the main focus and it allows us to get a good glimpse of his slightly stilted playing style. There are also solo passages by Davis and the ever-ingenious Haynes.

“McNeil Island” – named after a small piece of land in Washington’s Puget Sound – is a short ballad that reveals Hill’s more meditative side, though the sense of stillness it creates is quickly dispelled by Black Fire’s closing cut, “Land Of Nod,” which begins almost raucously thanks to Joe Henderson’s spirited blowing of the main melody over staggering, almost ramshackle rhythms. In truth, though, it’s a track defined by a subtle ebb and flow, between loud passages and softer, more pensive ones.

Though considered to be in the vanguard of avant-garde music, Andrew Hill most certainly wasn’t an apostle of free jazz. In fact, as Black Fire reveals, one of his distinguishing characteristics as a jazz composer was his frequent employment of form and structure, albeit in an unorthodox fashion. Hill’s music could seem oblique and cerebral, perhaps, but it was actually brimming with passion and refreshingly free of bebop clichés. It was also deeply personal and indicative of a highly original musical mind.

While Point Of Departure, recorded for Blue Note four months later, is rightly regarded as Hill’s magnum opus, Black Fire doesn’t lag very far behind in terms of its quality and significance. It, along with many of Hill’s other Blue Note sessions from the same timeframe, has aged exceedingly well. Over five decades after it was recorded, the music on Black Fire still burns brightly.