When art imitates life, JAY-Z doesn’t dramatize his past. As he proudly states on “No Hook,” don’t compare him to other rappers, compare him to trappers; he’s more Frank Lucas than Ludacris.

Before putting out his 1996 debut album Reasonable Doubt at 26 years old, Jay was in the streets building his empire since the age of 13. He’s utilized his street smarts and becomes a hip-hop mogul, where his entrepreneurial hustle gets him in corporate boardrooms and his business acumen is a source of inspiration. If we wanted to create a label, we’d study his time at Roc-A-Fella Records with co-founders Damon “Dame” Dash and Kareem “Biggs” Burke. If we wanted to be a music executive, we’d examine his time as President and CEO of Def Jam Records, evolving from an artist to leading a formidable roster that included Rick Ross, Fabolous, and Rihanna.

Listen to the best of Jay-Z here.

If we wanted to retire before the age of 50, we’d look at 2003, the time when he announced The Black Album would be his final piece of work. He sold out Madison Square Garden for his farewell concert, which was recorded for the Fade to Black documentary, a perfect end to an eight-album run. After music, he promised to focus on his entrepreneurial endeavors, among them: a deal with Reebok for a signature shoe line.

JAY-Z is like Frank Lucas; they both can’t leave the game that made them for good. Three years later, in 2006, Hov released a comeback album, Kingdom Come, but to mixed reviews. Critics didn’t find his rhymes on opulence and commercialism too appealing, and they weren’t into him being about his celebrity – after all, he was making tabloid headlines for dating Beyonce and being buddy-buddy with Chris Martin and Gwyneth Paltrow. He needed to reclaim his throne in hip-hop, but how would he motivate again?

In 2007, Jay watched a late-summer screening of the Ridley Scott-directed film, American Gangster. He was moved by the story of Frank Lucas, portrayed by Denzel Washington, a drug trafficker who operated in Harlem in the 60s and 70s. Lucas’ notoriety came from doing business with his direct supplier, allowing him to shipping large quantities of heroin to the U.S. from Vietnam. He related to the respect Lucas earned in Harlem for distributing his wealth, almost a direct parallel to what he earned in Brooklyn and the tri-state area.

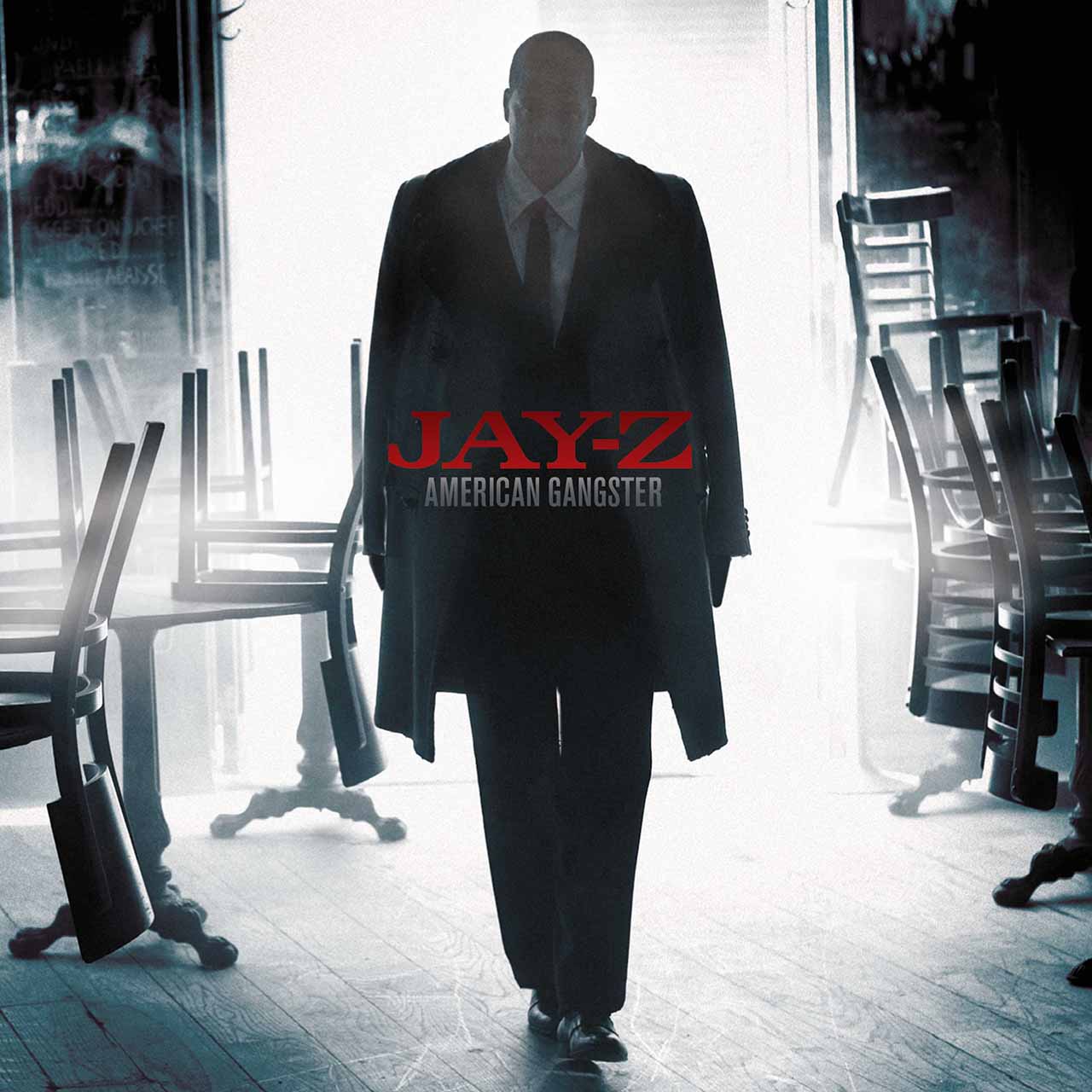

And so, the gangster Shawn Corey went to work on writing and recording his 10th studio album, American Gangster. Initially, Jay wanted to make the soundtrack to the film (Denzel also advocated for this), but it didn’t fit the film’s 1970s America setting. Instead, he spent four weeks completing a companion piece, loosely outlining the rise and fall of a drug dealer who grappled with emotional complexities as he dealt with his notoriety. When American Gangster was released on November 6, 2007, the album marked a professional milestone for Jay, selling 425,000 copies in its first week and earning his 10th chart-topping debut of his career.

Musically, the production is handled by Puff Daddy and the Hitmen, The Neptunes, Jermaine Dupri, No I.D., Just Blaze, and DJ Toomp. They were selected by Jay because he knew they could deliver the vintage backdrops he was looking for. Samples of Marvin Gaye, The Isley Brothers, Curtis Mayfield, and others gave the album its lush and cinematic moments. Collaborators who were in the studio with Jay saw that he played the film on the monitors above the recording booth during his sessions, immersing himself in a world that he once knew.

Within Jay’s catalogue, American Gangster is a reminder to the fans that looking back to bounce forward is a sign of maturity. While The Blueprint and The Black Album are obvious classics that cemented his Best Rapper Alive status, American Gangster is akin to 4:44 in that it is him expressing himself with unheard memories of his past, influencing future hustlers to maybe rethink their own reasons for entering the game. Dark days or triumphant ones, Jay took us on a journey. With dialogue from the film to drive his narrative forward, he’s aspirational (“American Dreamin’”), boastful (“Blue Magic”), paranoid (“American Gangster”), contemplative (“Fallin’”), celebratory (“Roc Boys”), ignorant (“Ignorant Shit”), liberating (“Success”) – just going through it all until his protagonist’s downfall. “To live and die in N.Y. in the hustle game” is not only a bar, but an absolutely truth.

In the same way anniversaries for iconic mafia films like Scarface and The Godfather are celebrated religiously, this album should be remembered for Jay’s legacy and his place in the pantheon of drug kingpins in hip-hop. True fans will always connect to this Hov because it’s a time capsule of his former life; he’s not the unwavering pop culture influencer here; he’s wearing a NY-fitted with the brim low, eloquently rhyming like he’s in the Marcy Projects again.

But these days, JAY-Z is more himself than Frank Lucas, constantly growing as a human with the goal of betterment, and righting his wrongs in a public platform so others can learn from his lessons.

Listen to the best of Jay-Z here.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in 2017.