As the 70s became the 80s, commercial Black music in the US was ruled by one style: disco. Funk, reggae and soul sat in the background, but the dancefloor’s most basic beat ruled. One record company had never failed to please the feet, bringing truly soulful sounds to dancers worldwide, and was happy to provide disco, funk, and soul too. In the 80s, Motown, the most ebullient, good-time label of the 60s, was still ready to party.

But the company no longer possessed a particular personality. Its classic sound was exploited as a retro, nostalgic matter, but when it came to making new music, Motown in the 80s was not remotely in love with the grooves of the past. However, some of the stars that built the company’s legend remained: Diana Ross, Stevie Wonder, and Smokey Robinson had always been Motown acts – and Smokey was its vice president. Berry Gordy, Motown’s founder, remained at the helm, though through the 70s he’d been producing movies such as Lady Sings The Blues (1972), which saw Diana Ross nominated for an Oscar for her portrayal of Billie Holiday, and Mahogany (1975), in which Gordy directed Ross. He initially refused the former Supreme the role of the youthful Dorothy in the 1978 movie The Wiz, based on The Wizard Of Oz, but the canny Ross, 33, found a work-around by approaching Universal Pictures, who were investing in the movie. According to the critics, Gordy’s initial instinct was correct – the Oscar-nominated Ross was now the lead in a flop. However, The Wiz marked Michael Jackson’s rise to adult prominence and his performance was widely praised.

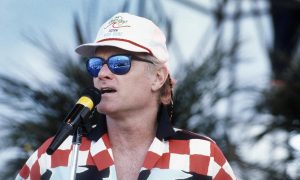

Diana Ross

Acting forays aside, Diana Ross continued to make alluring music through the second half of the 70s, but her last US No. 1 had been 1976’s “Love Hangover.” While records such as “The Boss,” “No One Gets The Prize,” and “It’s My House” made her a regular at the top of the US dance chart in 1979, Motown’s most glittering star had not quite ruled the mirrorball era as she might have.

Fearing that she was not dancing on disco’s cutting edge, Ross personally hired Bernard Edwards and Nile Rodgers of Chic to “turn her career upside down.” Her request was taken literally, with the disco maestros composing an album for her which included a track called “Upside Down.” But fate intervened; a backlash against disco, including record-smashing events and T-shirts bearing the motto “Disco Sucks,” gained a lot of publicity as the album was being mixed.

It was true that disco had excesses, such as “Disco Duck” and terrible dancefloor versions of swing-era ditties. But all musical movements have bandwagon jumpers, and the anti-disco campaign was a hype, perhaps with racist and homophobic overtones. But Ross grew nervous: her album with Chic was more disco than anything she’d done. Friends in the industry, including famed DJ Frankie Crocker “The Chief Rocker,” reportedly warned her that her status as soul’s leading lady was at risk if she issued her straight-up disco LP.

A spooked Ross took the tapes to Motown’s engineering wizard Russ Terrana, sped up some tracks’ tempos, re-recorded some vocals, and re-edited other songs to emphasize the vocals over instrumental passages, making the results more like a Diana Ross record than a Chic disco extravaganza. Edwards and Rodgers were not aware of this until the album was ready for release.

Though highly aggrieved when they heard the final mix, Diana was a runaway success, hitting No. 2 on the US album chart in 1980 without even an advance single to promote it. When Motown got round to issuing singles, “Upside Down” made No. 1 and “I’m Coming Out” hit No 5. The eccentric tale that was “My Old Piano” made the Top 5 in the UK. Was it due to Ross’ remix strategy, her vocal personality, or Chic’s golden touch? Probably a bit of everything, but Ross was vindicated in her actions. The following year, she left Motown and did not return until 1989’s Workin’ Overtime, which also marked a reunion between the singer and producer Nile Rodgers, despite the dispute over Diana.

Jermaine Jackson

Another long-standing Motown act made a commercial breakthrough in the 80s. Jermaine Jackson had been the only member of Jackson 5 to stick with Motown when his brothers moved on in 1975. His first solo album had been issued in 1972, but he never enjoyed the sort of success Michael had, though his singles performed respectably on the R&B chart and his 1973 revival of Shep And The Limelites’ “Daddy’s Home” went Top 10.

By 1980, Jermaine was overdue a hit, so he turned to another artist who’d graduated from being a Motown child star: Stevie Wonder. The pair created “Let’s Get Serious,” a funky yet romantic tune that was one of the biggest-selling soul singles of 1980. The album of the same name sold close to a million copies. At last, Jermaine had broken big and had “got serious”; however, though he went the extra mile, even cutting a fair-sized hit in 1982 with electro-punk pioneers Devo, “Let Me Tickle Your Fancy” (a likely influence on his brother’s smash “Beat It”) his next anthem would be on another label and didn’t arrive until the mid-80s.

Stevie Wonder

Stevie Wonder, whose genius had swept him serenely through the 70s, began the 80s delivering joyous tracks without compare. His October 1979 album, Journey Through The Secret Life Of Plants, might have caused some head-scratching, but it had been intended as the score for a documentary of the same name rather than a main Wonder opus.

Eleven months later, the next Wonder album proper, Hotter Than July, suggested he’d rule the 80s as he had the 70s, delivering the hits “Master Blaster (Jammin’),” a soaring tribute to Bob Marley and the glory of black musical unity; the gritty “I Ain’t Gonna Stand For It”; a mellow ballad in “Lately”; and ”Happy Birthday”, a celebration of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, which added weight to the campaign for the Civil Rights leader’s birthday to become a US national holiday.

1982’s The Original Musiquarium I gave us “Do I Do” and “Ribbon In The Sky,” and Wonder found time to launch his own label via Motown, Wondirection (yes, he used that name first), which delivered “The Crown” by Gary Byrd And The GB Experience (1983), another celebratory single with a sizzling slice of Wonder-fulness. His duet with Paul McCartney, “Ebony And Ivory,” was a 1982 US No. 1, and Wonder was prominent on an all-star version of “That’s What Friends Are For,” credited to Dionne Warwick And Friends and released for an AIDS charity. Wonder’s harmonica graced many a song by other artists, too, and he landed another big credit on Charlene’s hit single “Used To Be.”

Charlene, Smokey Robinson, and Rick James

Charlene’s success was a sign of how much Motown had changed in the decades since its inception. Charlene D’Angelo had been around the company since 1973 and had issued several flop singles before her “It Ain’t Easy Coming Down” became an easy-listening hit in 1977. She’d also co-written “One Day In Your Life” for Michael Jackson. In 1976 she’d cut “I’ve Never Been To Me,” which just about made the Billboard Hot 100, and Motown reissued it in 1982 after it started getting unexpected airplay. The song started selling heavily, but Charlene was not present to promote it. Nobody knew where she was. Detective work resulted in the singer being traced to Ilford, Essex, in the UK, where she was working in a sweet shop. She rejoined Motown and “I’ve Never Been To Me” became a worldwide success. It could not have been a less “Motown record” in the traditional sense: a ballad about a dissatisfied mother discovering her destiny, it was far more country than soul, but it suited the decade of Educating Rita and Shirley Valentine.

Smokey Robinson, as ever, managed to find a smooth adult sound that delivered soul, too; from time to time the Quiet Storm star unleashed an elegant smash to remind the world of his artistry, such as “Being With You” (1981) and “Just To See Her” (1987). He may have been a Motown executive with business on his mind and suffering personal problems, but he was still some kind of wonderful.

Motown still had its funk chops, too. Rick James was on fire in the early-to-mid-80s. The punk-funker scored heavily with 1981’s Street Songs, which included “Super Freak (Part 1),” the hit he’s most identified with today, and his next two albums, Throwin’ Down and Cold Blooded, maintained its standard. He also hit with “Ebony Eyes,” a duet with Smokey; produced several hits for the group he masterminded, Mary Jane Girls, including “All Nite Long” and “In My House”; and relaunched his own Stone City Band as an entity in its own right.

The Temptations, High Inergy, and Dazz Band

Another act James worked with, The Temptations, had returned to Motown after a period at Atlantic. James produced and performed on their 1982 R&B gem “Standing On The Top.” The group was now swollen by the return of their 60s and 70s stars David Ruffin, Eddie Kendricks, and Dennis Edwards, meaning there were seven singers on the album Reunion, all of whom were capable of handling lead vocals. Clearly this situation could not last, and Ruffin and Kendricks were out by the end of 1982 after tensions arose on tour. Edwards was next to go, which gave him the opportunity to cut “Don’t Look Any Further,” a 1984 hit duet with Seidah Garrett regarded as an 80s soul classic. Oli Woodson took over the Tempts’ lead duties and the following year they enjoyed their biggest hit for yonks in the punchy, advisory “Treat Her Like A Lady” (though its lyrics were something of an anachronism even then). The group would continue to cut R&B chart hits throughout the 80s, with former lead vocalists coming and going as the participants saw fit.

In the late 70s, Motown’s Gordy label had signed an act which deliberately styled itself after some of Motown’s 60s girl groups: High Inergy. Their biggest hits were released in that decade, notably their pop smash “You Can’t Turn Me Off (In The Middle Of Turning Me On),” but they remained reliable R&B chartists until 1983 thanks to the likes of “He’s A Pretender” and the strolling “First Impressions.” Their expressive lead singer, Vanessa Mitchell, deserved more praise than she got, with a voice that could have graced Motown’s classic era.

Dazz Band joined Motown in 1980, though the company had been aware of the group for several years, as they’d worked on an abortive Marvin Gaye album. Their biggest hit was 1982’s “Let It Whip,” a Grammy-winning chunk of super-tight groove. Though they deployed several vocalists and had some handy synchro dance moves like they’d been schooled in the 60s, their thang was really a modern electronic, tidy funk that sounded totally contemporary in the early 80s.

Commodores, Lionel Richie, and Teena Marie

If Motown had hoped Dazz Band would emulate the spectacular rise of Commodores, it was disappointed. Few funk artists could emulate Commodores’ ability to reach a mass audience. Their singles “Brick House” and “Easy” were stylistically very different, yet both were massive in ’77; and they’d arguably peaked with 1978’s Natural High, which featured the fluid “Flying High” and the unabashedly sentimental waltz “Three Times A Lady.” But the band wobbled when one of its two frontmen, Lionel Richie, quit in 1982. Though their foundation was funk, their biggest successes had been ballads, which Richie specialized in delivering. Their first post-Richie album, 13, sold significantly fewer copies than its predecessors, but Richie went from strength to strength.

Lionel Richie had already hit No. 1 in 1981 with “Endless Love,” a duet with Diana Ross, and he held that position four times between 1982-85 with soft-centred songs such as “Truly,” “Hello” and “Say You, Say Me,” though sometimes he missed creating floor-fillers, and hit with two of them: “All Night Long (All Night)” and “Dancing On The Ceiling.”

Remarkably, Richie put out three albums, then in 1986, at the peak of his fame, took a ten-year break. Commodores, meanwhile, also lost their other frontman, Thomas McClary, who released one album before quitting the business to take up gospel music. The group reunited for a 1985 tribute to fallen soul idols in “Nightshift,” and the single and the album of the same name sold heavily. It was their Motown swansong.

One further funk act signed in the 70s deserves mention: Teena Marie, the soulful songstress whose beats kicked butts. Four albums on Motown’s Gordy imprint made her a major cult figure among funkateers, and singles such as “Behind The Groove” and “Square Biz” moved feet on jazz-funk dancefloors in the UK. However, by the time she released her most “Motown-like” album, Starchild, which featured a moving tribute to the late Marvin Gaye, she was no longer a Motown artist.

DeBarge, Rockwell, and the Four Tops

Having nurtured the family soul superstars of the 70s, Jackson 5, Motown set out to do it again for the 80s with DeBarge, featuring six, sometimes five siblings of the same surname, of which El DeBarge was acknowledged as the biggest star. Theirs was not a rapid rise to fame, though they gained popularity through tour support slots and their record sales rose across the course of four years, climaxing with 1985’s poppy, Latin-influenced groove, “Rhythm Of The Night.” Solo records followed from El DeBarge (whose first single, 1986’ “Who’s Johnny,” was his biggest), Chico (“Talk To Me”), Bunny, and Bobby. Motown boss Berry Gordy was reputedly surprised to learn that his own family had a young artist, Rockwell (AKA Kennedy William Gordy), supposedly signed to Motown on the strength of demo tapes without his dad’s knowledge. Rockwell’s three albums delivered one major hit, his 1984 debut single, the paranoid funker “Somebody’s Watching Me.”

Some original Motown artists who’d walked away found the door open when they returned. Four Tops made it explicit with 1983’s Back Where I Belong, produced by Holland-Dozier-Holland, another returning team which had delivered many of the group’s amazing 60s records, but three albums did not restore this group’s chart status and they left again in 1988. Older soul stars with no previous Motown association, such as Wilson Pickett and The Pointer Sisters, tried their luck on the label; neither made it beyond one album.

Stevie Wonder never left, and hit heavily in the mid-80s with “I Just Called To Say I Love You,” “Part-Time Lover” and the more soulful “Overjoyed” and “Go Home.” His success levels tapered off in time, however; not a result of Stevie’s music changing but because of more a generational shift: younger fans needed new heroes.

Motown in the hip-hop era and beyond

This was a problem for Motown. It had not signed the equivalent of its classic artists who could deliver hit after hit, and cutting-edge African-American music was more focused on hip-hop, modern R&B, and house than the soul Motown had helped forge. The company’s dalliances with hip-hop were, for the most part, unsuccessful: funk band-turned-rappers General Kane cut the decent if not groundbreaking album In Full Chill, which featured the thumping message of “Crack Killed Applejack,” an R&B hit in 1986. The label signed Warp 9 once the futuristic electro group was no longer quite so futuristic.

A fine 1989 album from Jesse West, No Prisoners, did not sell heavily and West later hit his stride elsewhere as the successful producer-rapper 3rd Eye. Motown snapped up the super-talented Queen Latifah in 1993, but only her first album for the label, Black Reign, and its accompanying single “UNITY,” did big business, with the latter landing a Grammy. Latifah’s acting career was starting to boom by this point, resulting in a gap of five years between her two Motown albums.

The company also worked with less likely acts such as Chris Rea, licensing one album for the US; though it boasted a seasonal song, it was no “Driving Home For Christmas.” Bruce Willis’ The Return Of Bruno (1987) sold soul material to a mass market, slotting neatly into the era’s peculiar penchant for white actors covering ancient soul hits (see also The Commitments and The Blues Brothers movie). … Bruno featured the likes of The Temptations and June Pointer in a fantasy-fulfilling project for the Die Hard star.

In 1988, Berry Gordy sold his shares in the music corporation he’d created, and the label became part of MCA and, subsequently, Polygram and Universal. Gordy had ensured his role would be taken by Jheryl Busby, head of MCA’s black music division. Busby was African-American and steeped in the new R&B, which fused soul and hip-hop. He made some crucial signings, such as Boyz II Men, Johnny Gill, and Another Bad Creation, all of whom kept Motown’s name in the public eye. Marketed as an R&B group with doo-wop and soul awareness, Boyz II Men sold 25 million albums, and their debut, Cooleyhighharmony, contained six massive singles, among them the classic ballad “End Of The Road” (which was added to the album after spending months at US No. 1) and the roots-acknowledging “Motownphilly.”

Motown in the new millennium

The development of major R&B stars at the label ensured that the company would not be surviving on the remixes and repackaging of its classic material that it naturally also issued. When the new millennium dawned, the likes of Erykah Badu, Ashanti, and Nelly would be proud to see the Motown brand on their records. To the casual observer, however, it may have appeared that, after three decades at the top, Motown was no longer capable of encapsulating “The Sound Of Young America.” Not so.

Gordy’s label had always known when to reinvent itself: after taking the Detroit sound around the world in the 60s, in the 70s it relocated to Los Angeles, the epicenter of the entertainment industry, to ensure its continued relevance. Faced with yet more shifts in the musical landscape, in the early 21st century Motown once again changed its focus, this time alighting on Atlanta, the beating heart of modern-day hip-hop.

With a new youth culture to appeal to, the label’s famous quality control showed no signs of faltering – quite literally, as it teamed up with the Atlanta-based label Quality Control Music. Together they would issue cutting-edge sounds that helped bring trap music and a new generation of hip-hop stars to the world.

Looking for more? Discover the best Motown songs of all time.