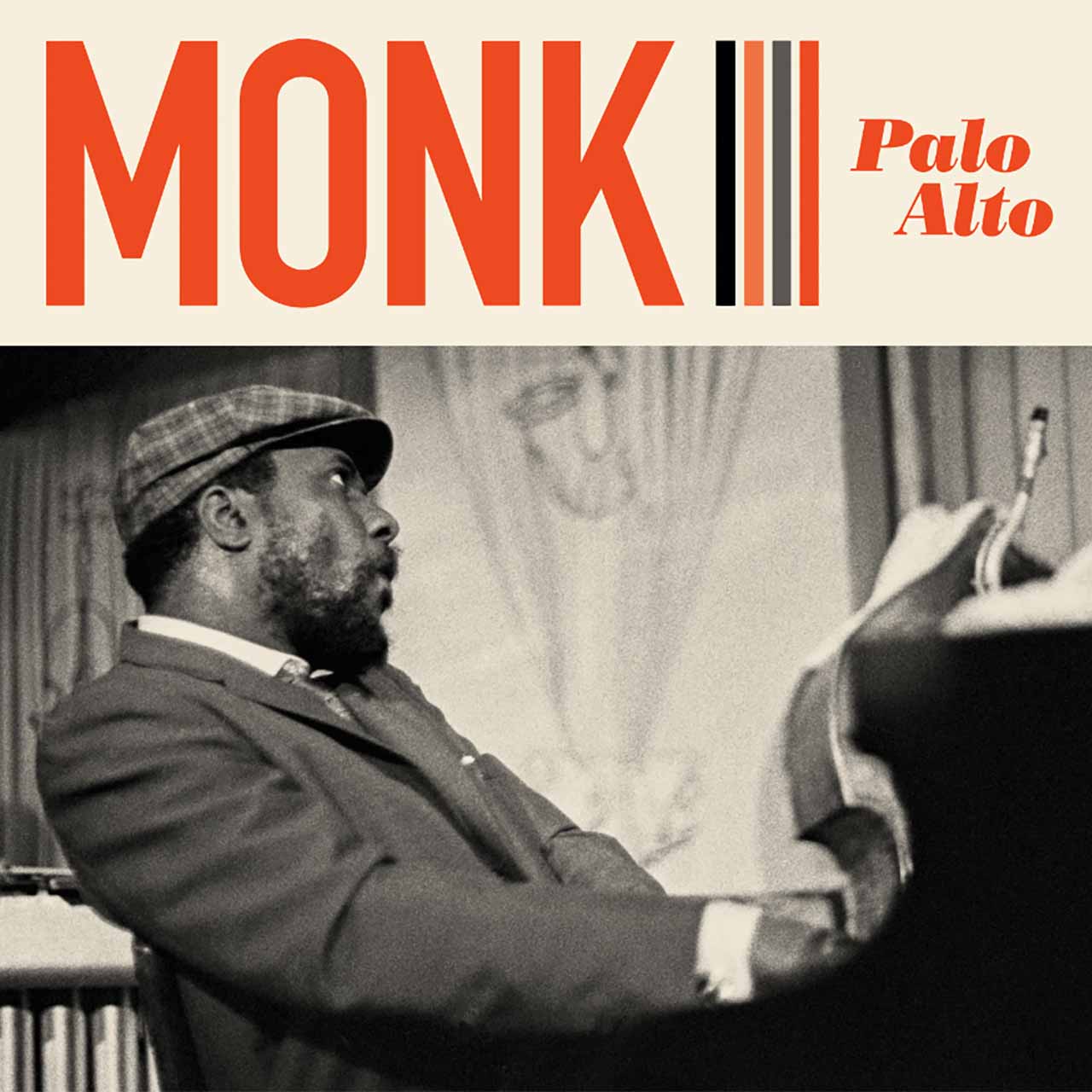

For most of the citizens in the Bay Area city of Palo Alto, October 27, 1968, may have seemed just like another Sunday, but at a local high school, something extraordinary was happening: jazz legend Thelonious Monk was playing a concert.

Thelonious Monk playing a concert, of course, wasn’t all that out of the ordinary in 1968. What was odd was the promoter was an enterprising 16-year-old white Jewish schoolboy called Danny Scher. “My two idols were Thelonious Monk and Duke Ellington,” says Scher, now 68, recalling how the Monk concert came about. “I had a dream of bringing them to my high school.”

Buy Thelonious Monk’s Palo Alto here.

The teenager had already organized two previous high school jazz concerts and was friends with a local promoter, Darlene Chan, whom he helped out occasionally. He told her about his dream and she said, “here’s Monk’s manager’s number, give him a call.” Scher followed her advice and was told by the pianist’s manager that Monk would appear for $500. After a deal was agreed, Scher was sent promo pictures, copies of Monk’s latest record, and a contract. “I was not old enough to sign it, so I gave it to the school principal to sign,” he says, adding that the principal only agreed to do it because it was a benefit concert. All profits from ticket sales would go to the school’s International Club, which supported schools in Kenya and Peru.

Promoting the concert

Scher worked hard to promote the concert. “I printed up posters, put ads in stores and put together a program,” he remembers, “so that even if I sold very few tickets, we’d have enough money to pay Monk. Tickets were $2, and if you were a student, they were $1.50. Back then, that was cheap.”

Even so, ticket sales were so slow that Scher decided to advertise the concert in East Palo Alto, an unincorporated area (at the time) located just north of Palo Alto. In 1968, East Palo Alto was considering a vote to change the area’s name to Nairobi. It was also regarded as a no-go area for whites. “There were posters all over East Palo Alto saying ‘Vote Yes On Nairobi,’ and there I was putting up my Thelonious Monk concert posters right next to them,” laughs Scher. “The police came up to me and said, ‘you’re a white kid, this really isn’t safe for you,’ but I wasn’t thinking like a white kid, I was thinking like a promoter who had to sell tickets.”

Monk’s visit came at a time when the United States was beset by racial tensions. The assassination of Civil Rights leader, Martin Luther King Jr., in April 1968 only heightened the country’s sense of division. But Scher continued putting up posters and began talking to some intrigued locals, who didn’t believe Monk would turn up at an all-white high school. “They were skeptical, so I told them, if you don’t believe Monk is coming, then don’t buy a ticket – but come to the high school parking lot, and when you see him, buy one.”

A temporary snag

Another twist in the tale came a few days before the concert when Scher called Monk to go over the concert arrangements. The pianist, who was in the middle of three-week club residency in San Francisco, shocked the schoolboy by saying, “I don’t know anything about it.” Monk told Scher he already had a gig booked that night and also had no way of getting to and from Palo Alto. “My brother can get you, he’s old enough to drive,” responded Scher, which satisfied Monk, who then agreed to play the concert.

“As my father already had a gig that day, I have a strong feeling that he said yes because it was a 16-year-old kid contacting him,” says Monk’s son, T. S. Monk, who produced and helped in the audio restoration of the Palo Alto concert tape. “It’s very unusual and outside the box; very Thelonious Monk.”

The concert

Arriving at the school parking lot in the Scher family’s station wagon, Monk and his band – tenor saxophonist Charlie Rouse, bassist Larry Gales and drummer Ben Riley – were met by several hundred people, both black and white. The group appeared on stage at 2 pm, following a couple of local support acts. Monk played a 47-minute six-song set, which included vibrant versions of his classic tunes “Well, You Needn’t,” “Blue Monk,” and “Ruby, My Dear.”

“It brought me chills because the energy of the concert was so high,” recalls Scher, who went on to become a west coast concert promoter and worked for many years with the legendary Bill Graham. “Everything’s a little faster, and the solos are longer than usual. When I first played the concert to T. S. Monk, he knew right away that his father was feeling good.”

“He was playing his ass off, and the band was really cooking,” laughs T. S. Monk, who says he first became aware of the recording 20 years ago but at the time wasn’t able to give it any attention. “I could hear that he was feeling really good. His best performances have always been live: there’s a different kind of energy and freedom than on his studio recordings.”

The recording

The fact that a recording of the concert exists at all is down to a school janitor who volunteered to capture it on his mono reel-to-reel machine. He gave the ¼-inch tape to Scher, who then kept it in a box for over half a century. “There’s a social media campaign to find out who the janitor was,” reveals Scher. “Based on the quality of the recording, he really knew what he was doing.”

Looking back, T. S. Monk believes the Palo Alto concert has new relevance. “I think it’s very appropriate to release it right now in America [in 2020] given its back story,” he states. “It’s a message of unity, which is something that we need on planet Earth right now.”

“It shows that music can bring us together,” says Scher. “I like to think that on that afternoon 52 years ago, everyone became colorblind.”

We are re-publishing this feature on the Palo Alto concert, which was originally published in 2020, on the anniversary of the concert in 1968. Buy Thelonious Monk’s Palo Alto here.